LEA is collecting dates of ice-in and ice-out for our area lakes. If you’re a keen lake observer, we could use your help!

Ice-out (or breakup) dates have been collected since the 1800s and have been used as indicators of climate change. That is only part of the story and increasingly scientists are interested in the duration of ice cover on lakes. This is often a better proxy for air temperature trends and can impact lakes by affecting things like water levels, extent of anoxia, and recreational use. To get duration you need ice-in (or freeze) dates.

Ice-out is defined by the state as when you can navigate unimpeded from one end of the water body to the other, or by the National Snow & Ice Data Center as the date of last breakup observed before the summer open water phase. Ice-in is the first date when a lake is observed to be completely covered with ice. Sounds easy, right? But, lakes can freeze and thaw multiple times in late fall before finally freezing over and our big lakes often don’t freeze all at once. We are most interested in the initial ice in date in the fall, and the ice-out date in the spring. Heads up – skim ice that melts as soon as the sun comes up should not be noted as ice-in, so have the morning coffee and email Ben around 11. 😉

Send your observations to us by emailing Ben@mainelakes.org. Be sure to include your name, lake, date, and any notes you want to share (like, loons were here 2 days ago, it’s been wicked cold, the lake thawed after ice-in, etc.) There are several organizations that collect ice data from around the state. LEA collects and shares data from our service area with the Lake Stewards of Maine (formerly VLMP) and (ice-out data) with the Maine DACF.

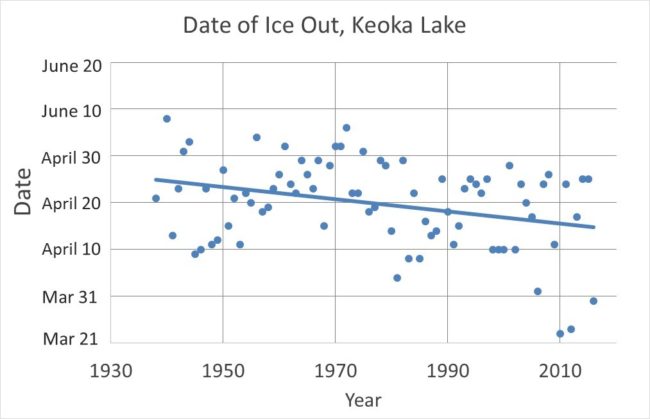

Keeping a record of ice-out dates is important for understanding lake water quality in an individual year as well as over time. The trend in ice-out dates shows that they’re getting earlier over time, as this graph from Keoka Lake shows. Ice-out on Keoka Lake now happens 10 days earlier, on average, than it did 78 years ago.

Early ice-out paves the way for a longer period of stratification in the summer, which can increase the magnitude of oxygen depletion occurring at the bottom of a lake. This loss of oxygen may lead to fish kills, internal phosphorus release, and algae blooms – all bad news for our lakes.