MLSC Initiatives

In the last several years, LEA has augmented its traditional lake sampling program to incorporate new and advanced tests and monitoring techniques. These initiatives are a result of knowledge gained from partnerships that we have developed while working toward Maine Lake Science Center goals. Below is a brief summary of some these initiatives.

Maggie and Shannon head out with monitoring gear on Woods Pond

Regular winter monitoring of lake systems in western Maine

The winter lake monitoring project kept Ben, Maggie, and Shannon quite busy in 2022. The three made multiple visits to 13 different lakes for a total of 32 different trips. And that was in spite of a shorter “safe ice” season — ice was starting to pull away from the shore in spots during the last trips in mid-March. They measured ice thickness and collected the usual sonde profiles on each trip, but they also measured water clarity, light levels, and phosphorus. They imaged many of the samples using our FlowCam, producing our most detailed view of winter lake algae communities to date.

The Maine Lake Protection and Research Collaborative

Lake monitoring and research support healthy land and water and underpin efforts to stabilize, improve, and restore water quality. Educating students and the public builds environmental ethics and practices. LEA strives to help strengthen community organizations, integrate infrastructure with natural landscapes, and help communities adapt and respond to climate change. In collaboration with other organizations, LEA has developed a working model approach: the Maine Lake Protection and Research Collaborative. The Collaborative engages a multi-disciplinary community of academic researchers, state and federal agency staff, and non-government organizations to collaborate with the common purpose of identifying ‘needs and barriers’ for the protection of Maine’s precious lakes.

One of the first priorities under the Collaborative focused on establishing regional hubs to provide training and resources to empower lake organizations to increase monitoring and program capacity. To do this LEA worked with grant funders to create, provide, and distribute “monitoring packages” that allow for expanded research at regional hubs and lake associations that have staff capacity. Packages were developed based on expressed needs and desires of individual organizations with input from a coalition of large lake associations in the state. Packages were developed for 7 Lakes Alliance (formally the Belgrade Regional Conservation Alliance), the Midcoast Conservancy, the Lake Stewards of Maine (formally Volunteer Lake Monitoring Program), the Rangeley Lakes Heritage Trust, 30 Mile River Watershed Association, and the Cobbossee Watershed District.

Ben on LEA’s auto-analyzer

To help better understand and document algae and nutrient concentrations in the state, LEA added in-house lab fluorometry and spectrophotometry to the Science Center lab with foundation funding. Our research director is using these instruments to compare field and lab chlorophyll data and to develop calibration curves to compare results from the two methods. Analyzing chlorophyll fluorometrically can significantly reduce long-term lab costs. This was identified from past research retreats as a need in the state and a priority for the Collaborative.

We have also purchased and set up an auto-analyzer to measure total phosphorus and nitrogen in lake water samples. This nutrient analyzer is a continuous flow analyzer, which pumps samples through narrow tubing and sequentially adds chemicals that produce a color proportional to the amount of phosphorus present. All of this happens automatically once we start the machine running. This instrument saves time over other methods and running our samples in-house will greatly reduce our annual analysis costs and further elevate the capabilities of the Science Center as a research hub.

A new instrument, the FlowCam from Yokogawa Fluid Imaging Technologies, was purchased from a Maine-based company in Scarborough, which grew out of research done at Bigelow Laboratory in East Boothbay. The FlowCam uses flow imaging microscopy to rapidly capture particle images and count and measure those particles. With it, LEA can semi-automatically identify and quantify algae and other microscopic organisms in lake water. The FlowCam is a cost-effective way to detect changes and trends in lake algae, including the presence and growth of harmful species.

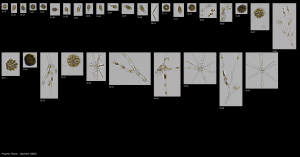

FlowCam pictures of Highland Lake samples

Flow imaging microscopy works by passing fluid-based particles (e.g., algae) through a flow cell, past a magnifying objective and a light source. A camera captures images of each particle and the software analyzes each image for many different shape and size characteristics. The identity and density of each unique particle (algae) type is then determined. What would take hours by manual microscope methods is accomplished in minutes.

Optical brightener study

During the summer of 2019, LEA worked with an army of volunteers who collected samples to help determine the impact of septic systems on our lakes. As most homeowners know, wastewater from our homes and camps flows into a concrete septic tank where solids settle out and then the liquids continue on to a buried field of perforated pipes or chambers where the remaining water can filter into the ground (at least that is how it is supposed to work!). But many systems are old and they may not be functioning properly. This could lead to wastewater, which contains both nutrients that fertilize algae and human pathogens, getting into the lakes and ponds where we swim and recreate. To help determine if this is happening, volunteers collected water samples up and down the shores of lakes. These samples were then analyzed for the presence of optical brighteners. Optical brighteners are compounds found in some paper products and laundry detergents to make paper and fabrics “whiter and brighter”. Their presence alone in a sample of water is not a health issue, but it does indicate that septic systems may not be properly treating wastewater. This could mean that other, more harmful contaminates are getting in our lakes.

The first round of sampling took place in early July and the second round of sampling took place in late August/early September. Volunteers revisited sites that tested positive at the first sampling and also sampled new locations to increase the coverage. Out of 105 samples in July and 78 samples in August and September, 33% and 41% respectively tested positive for optical brighteners. Optical brighteners by themselves do not definitively identify septic system failures; at the very least, an additional indicator should be measured at the same time. We had hoped to expand this project in 2020 with simultaneous testing for other indicators of waste contamination, like E.coli, to better quantify the extent of the problem; however, this had to be postponed due to health restrictions during the pandemic. Please stay tuned and remember to pump your septic tank!

To help increase monitoring and education about blue green algae blooms, the MLSC has been hosting cyanobacteria (blue-green algae) workshops with EPA region one scientist Hilary Snook. Following training sessions, monitoring kits are offered to participants to allow them to institute their own cyanobacteria monitoring.

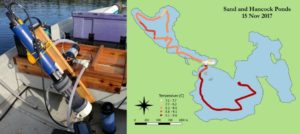

Under the umbrella of the Maine Lake Science Center, LEA has also begun acquiring new information on the chemical, biological and physical processes that occur within lake systems using multi-parameter monitoring probes called Sondes. These instruments acquire geo-referenced data simultaneously on turbidity, pH, oxygen, temperature and algal populations. One initiative we are implementing with this equipment is to spatially map the surface water quality of lake systems. This project uses a boat-mounted, flow-through system to generate rapid, high intensity measurements of surface conditions all over a lake. Interpolation of these survey data produce snapshots in time of whole lake status. This type of high-resolution, spatial assessment has been done by a few other researchers in the country, but the methodology is still fairly new.

Sonde and flow-through mapping

Using this flow-through instrument, LEA surveyed 10 lakes in 2019: Keoka Lake, Trickey Pond, Sand Pond, Woods Pond, Moose Pond (main basin), McWain Pond, Middle Pond, Peabody Pond, Hancock Pond, and Back Pond. Each survey data was analyzed and interpolated to produce maps of physical and chemical conditions across each lake’s surface. The results of these findings have been shared with partnering lake associations. In the summer of 2020, two event-driven surveys were done on Long Lake to assess conditions before and after a major rain event (see https://mainelakes.org/stormy-weather/).

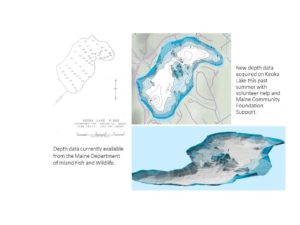

Another objective identified through the Collaborative is the need to acquire more high-accuracy depth data (bathymetry) on lakes. Using portable, GPS-enabled, depth mapping units (aka fish finders) we surveyed nine lakes in our region in 2017, 12 in 2018, and 15 in 2020. This new data is extremely detailed and will provide an accurate way to quantify the impacts of oxygen depletion and overall susceptibility to internal phosphorus recycling. The project was supported by the Maine Community Foundation. LEA shares the methodology so other lake associations and lake stewards can take on similar work.

Another objective identified through the Collaborative is the need to acquire more high-accuracy depth data (bathymetry) on lakes. Using portable, GPS-enabled, depth mapping units (aka fish finders) we surveyed nine lakes in our region in 2017, 12 in 2018, and 15 in 2020. This new data is extremely detailed and will provide an accurate way to quantify the impacts of oxygen depletion and overall susceptibility to internal phosphorus recycling. The project was supported by the Maine Community Foundation. LEA shares the methodology so other lake associations and lake stewards can take on similar work.

On the policy and education fronts, we have been working to identify, educate, and inform direct and indirect stakeholders to build support for protection and restoration of Maine lakes. In November of 2017, LEA hosted a Watershed Educator Retreat at the Maine Lake Science Center. At the meeting, educators from around the state shared lesson plans, materials, specific activities, and overall strategies to improve offerings and bolster support for watershed and ecology based programming. Smaller focus workgroups were created to share resources and plan for future meetings in different locations, such as regional lake hubs, to ensure educators from all parts of the state can participate. Another multi-organizational education meeting, in collaboration with the Gulf of Maine Research Institute, to connect regional educators with interactive watershed science-based curriculum took place in July 2018 and a Sea Level Rise workshop in July 2019. In collaboration with the Maine Forest Service (MFS) we continue to offer walks in the woods to learn about watersheds and our local forests. We hold walks for teachers to become more familiar with the park behind their school and general nature walks to build connection to place. In the fall of 2019, the MFS, Project Learning Tree, and LEA hosted a workshop for college professors of education students.

The MLSC offered “Lake School” classes and courses for teens and adults interested in expanding their knowledge of lake and watershed systems. Educational and training opportunities took place in 2019, including: a three day immersive field studies course on lake ecology; a course to build your own water monitoring equipment; an accredited course for real estate agents on lake water quality and property values; and a four-day course for kids to explore nature through hands-on activities at our Holt Pond Preserve. After piloting programming in our service area, we will export as much as possible to regional hubs and conservation organizations throughout Maine. In July of 2021 the 3-day Lake Ecology course for high school students resumed and took place again in 2022.

Real estate agent course taught by LEA and Eaton Peabody Law Attorneys

core sampling on Long Lake

The MLSC policy team develops physical and social science-based public policy to encourage behavior change in order to implement the initiatives needed to sustain lake resources and services. In 2018, a steering committee was formed to convene a series of workshops aimed at developing or revising land use standards needed to bring lake protection up to date. Workshops were held at the three regional hubs and Maine Audubon. These involved lake advocates, staff from several agencies, lake association personnel, municipal officials, and the general public – many with extensive expertise in land use policy. The emphasis was on developing new standards that will allow policy makers and advocates to choose from a “menu” of options to customize management of individual lakes or lake regions. The current effort is to educate and involve myriad groups and individuals to create the political force necessary to successfully enact proposals to achieve our ultimate goal of protecting Maine lakes for future generations.

Policy meeting at Maine Audubon

Surveying erosion on a Bridgton road

We are also taking on initiatives at a watershed level. One of these projects is a new digital approach to erosion surveying, which helps assess the impact of climate change on stormwater infrastructure. The new method we are pioneering requires only one or two surveyors and a smartphone. Data entry, compilation, and analysis are fully automated. This method of surveying has great potential for the environment and public works departments. The functionality of a live, searchable map and a dynamic database make the product user-friendly. With foundation help, LEA developed a detailed handbook so other towns and lake organizations can easily replicate the process. Being able to track stormwater infrastructure problems is very important since most sediments and nutrients reaching lakes come from stormwater runoff. The handbook is available at https://mainelakes.org/stormwater_survey/, and we have developed an exportable survey that is ready for immediate use.

Other ongoing projects include:

Gloeotrichia echinulate monitoring. This species of algae is a type of cyanobacteria that dominates some low-nutrient lake systems in late July and early August. It is able to thrive despite low nutrient levels because it collects phosphorus from sediments before entering the water column. MLSC and LEA staff have been collaborating with Dr. Holly Ewing of Bates College in Lewiston, Maine on much of this research in the Lake Region.

Gloeotrichia monitoring on Long Lake

Temperature is one of the most fundamental and important characteristics of a lake ecosystem. Tremendous amounts of temperature data have been collected in several lakes using automated temperature sensors. Sensors are attached to a floating line at the deepest part of the lake, each collecting readings at a discrete depth every fifteen minutes throughout the spring, summer, and fall.

Algae are the basis of lake food webs. These microscopic plants can tell us a great deal about how a lake is functioning. Through assistance from the Portland Water District and the Bigelow Laboratory for Ocean Sciences, we have developed an algae monitoring program that identifies and counts each algae present in pelagic water samples. The LEA/MLSC staff have made significant progress on expanding enhanced monitoring efforts.

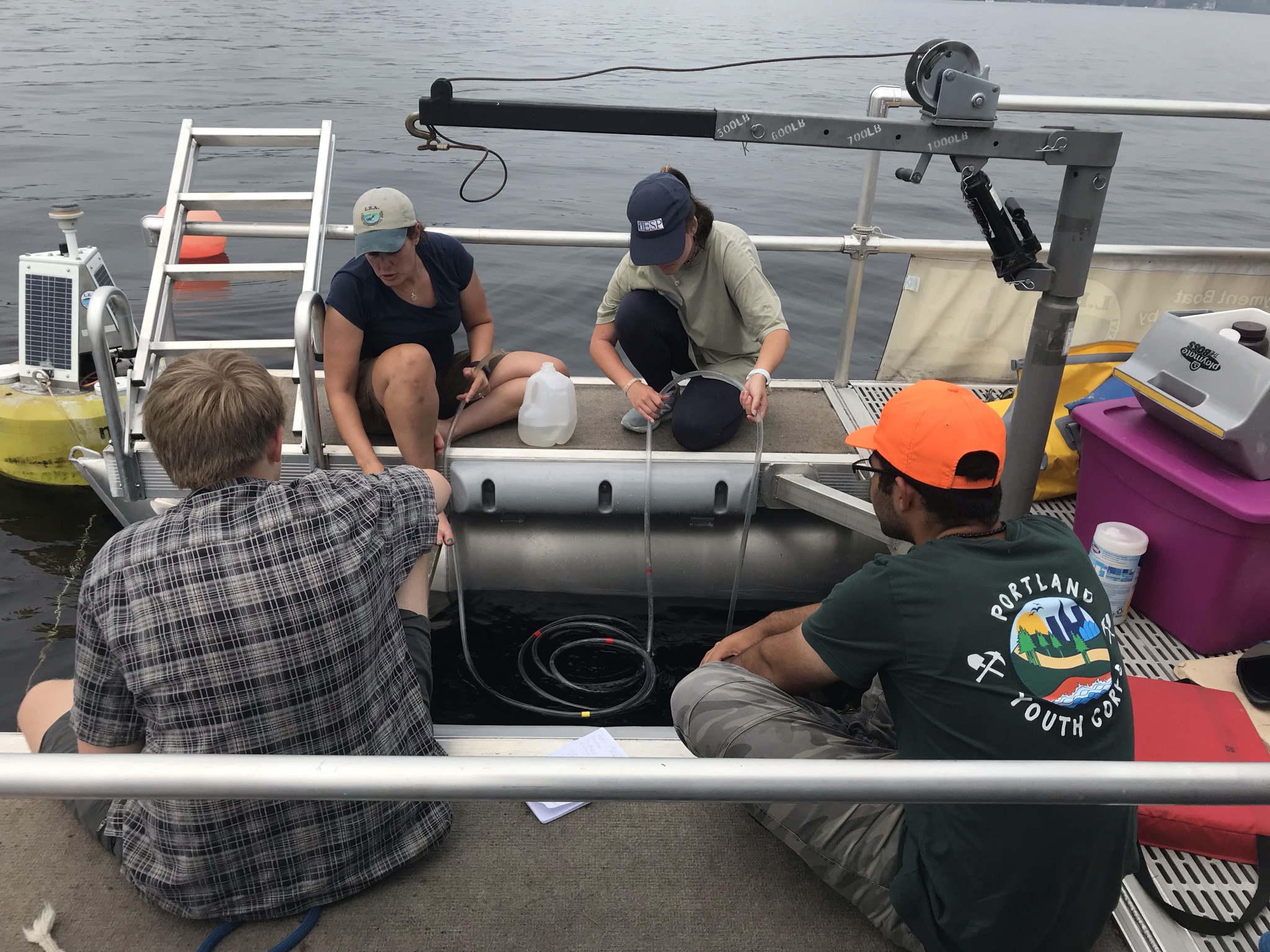

Highland Lake and the North basin of Long Lake are home to automated water monitoring buoys, which measure temperature, oxygen, clarity, chlorophyll, and weather levels every 15 minutes at the lake’s deepest point. The buoys are part of the Global Lake Ecology Observation Network (GLEON) network, a collection of lake monitoring sites located all over the world.

The deployment of the buoys is an effort to gather significant data and better understand how vulnerable our lakes are to algae blooms.

The deployment of the buoys is an effort to gather significant data and better understand how vulnerable our lakes are to algae blooms.

Sediment chemistry, in particular aluminum to iron and aluminum to phosphorus ratios, can predict whether or not a lake will experience internal phosphorus recycling. This detrimental process releases stored phosphorus from sediments, fueling algae growth and creating a destructive positive feedback loop in lakes with hypolimnetic (deep water) oxygen depletion. Drs. Stephen Norton and Aria Amirbahman of the University of Maine, Orono (UMO) were part of the group of researchers who first discovered this phenomenon. To better understand the influence of these element ratios in our region, LEA sampled sediment from many local lakes and had it run at the UMO Sawyer Lab under the guidance of Dr. Jasmine Saros.

Aluminum and iron sediment sampling

At the same time, Highland Lake and Long Lake were the subjects of a paleolimnological sediment study. This study analyzed changes in the sediment diatom record going back about 400 years. Analysis was carried out through collaboration with Dr. Jasmine Saros and researchers from the Climate Change Institute at the University of Maine.

Deep Sediment Coring on Highland Lake