The mission of the Maine Lake Science Center is to foster and sustain initiatives that will assure the long-term resilience of freshwater systems and communities. The Center will use an interdisciplinary solutions-oriented science approach, known as sustainability science, to link science with decision maker and policy development needs at municipal, state, and federal scales.

The Maine Lake Science Center was established by the Lakes Environmental Association (LEA) in 2015 to help initiate and support a new generation of lake protection. The Center facilitates partnerships between academic researchers, lake associations, decision makers, educators, citizens and land use professionals, incorporating an interdisciplinary approach to promote policy upgrades and build communities that can effectively advance lake sustainability.

Nearly 40 years ago, the Maine Legislature made a dramatic commitment to Maine’s lakes when it mandated shoreland zoning. This far-sighted act was generally well-accepted by citizens because Mainers could see their lakes were being damaged and cared enough to accept zoning.

It was not until 1990 that the next generation of lake protection came along. The Maine Department of Environmental Protection (DEP) developed a method to estimate the phosphorus pollution impact that a specific development would have on a lake. This was a significant breakthrough since it allowed for consideration of cumulative impact from all land uses in a lake’s watershed. LEA wrote a companion handbook for the DEP that outlined a process for producing a watershed inventory.

Maine lakes are degrading and we have no comprehensive method of determining their rate of decline. Lake Auburn’s unexpected algae bloom (2012) is a vivid example of a lake’s abrupt and unexpected decline in water quality. Judging from oxygen and nutrient levels in the 41 lakes LEA monitors, there is the potential for this pattern to be repeated throughout the state. Lakes are the backbone for the economy of hundreds of Maine towns, but monitoring standards have not kept pace with science, and we have done an inadequate job of educating decision makers, interest groups, and landowners. Protecting lakes means fully understanding what is going on in their watersheds and their waters in order to make the case through research and education for the public to support the types of management tools that are needed to avoid the “Lake Auburn Syndrome”. We have an opportunity to take the type of bold initiative that Maine legislators took in 1973 to protect a priceless and increasingly endangered resource. LEA believes the science of lake protection needs to be harnessed to allow us to protect water quality for future generations and our economy. And, education and a positive experience in the natural world complement scientific knowledge in promoting the changes that will be needed.

How the objectives will be accomplished

Research

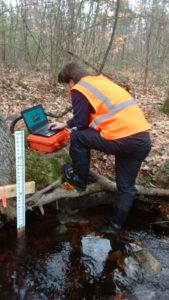

LEA has established the Maine Lake Science Center (MLSC) to attract world-class researchers and to support and empower those already doing research in Maine. We have formed a Lake Science Advisory Board with researchers from Maine to Lake Tahoe to guide the Center’s work, representing a full range of disciplines. At the Board’s first meeting in 2013, it was clear that much more could be done to network those who are working in the field. That year LEA hired its first researcher to expand traditional testing parameters and help with the networking challenge. In January 2017, our new Research Director began work at the Center, establishing a new lab and beginning lake research.

LEA staff spent five years visiting lake centers around the country to learn their methods and establish relationships. This valuable experience helped us shape our vision for the Maine Lake Science Center. Each place we visited added dimension to the vision and everyone we met was excited about the project and its importance.

One of the basic needs for researchers is housing. Meeting space, storage space, and lab facilities are other essential requirements. The Center offers all of these resources and a sixty-seat conference room available to conservation organizations and civic groups.

Education

LEA has a rich and long history of natural resource education, beginning more than 25 years ago. Education at all levels is essential for accomplishing project objectives since we ultimately seek to modify behaviors, policy and methodologies. Before any of these changes can effectively be made, there must be a clear showing of the practicality and scientific basis for the changes. We will need to rely on the same support-through-understanding and knowledge-to-action that helped the legislature pass shoreland zoning laws in the 1970’s.

While research is the pinnacle of the educational process, LEA has built a complex education program that reflects our belief that each interest group and age level has a stake in water quality and should be addressed in a separate and unique way. We have two full-time educators who oversee our program, but all staff members are engaged in some form of education. Target audiences are diverse but are part of a holistic effort to gain broad-based understanding and support:

Outdoor Learning and Recreation

The book Last Child in the Woods: Saving Our Children From Nature-Deficit Disorder was a sentinel for those involved in environmental education. LEA’s emphasis on conservation lands is based on the belief that getting kids and even adults into the natural world is the first step for instilling an appreciation for our natural resources. Most of our educational programs combine fun in the outdoors and learning. The 700-acre Holt Pond Preserve epitomizes the union between recreation and education. It provides a marvelous outdoor classroom for hundreds of kids each year. The preserve also allows hunting, fishing, trapping, canoeing, and snowmobiling. Hiking and cross-country skiing are popular as well.

The 66-acre Pondicherry Park offers a rare opportunity to get into the woods right in downtown Bridgton. The park mirrors the Holt Pond recreation-education model and is receiving heavy use because of its convenient location. The MLSC property is adjacent to the park and effectively expands the park’s acreage by 18 acres. LEA allows park users to utilize a parking area as an entryway from Willett Road, just off Route 302. Trail extensions link the Center with Pondicherry Park. The Pinehaven Trail, a forest interpretive trail with a low elements challenge course on Center property, is the first outdoor education resource of several planned. Work has begun on trails at the Highland Research Forest at Highland Lake in Bridgton.

Evidence of Urgency and Need

The urgency for the monitoring and research components of the Maine Lake Science Center project are highlighted by the experience at Lake Auburn and the vulnerability of hundreds of other Maine lakes. Prevention of water quality degradation is the goal. Remediation is enormously expensive and can never achieve a return to historic water quality. There was no focal point for lake research in Maine. Much of the research went unnoticed. It was only after we began to examine the research that we learned about the three new and vital parameters we have adopted into our testing protocol. They are directed at assessing the vulnerability of a lake to algal blooms. The Maine Lake Science Center now serves as a mechanism for collaborations and communications to help stem the tide of water quality decline.

Outdoor and natural resource education is becoming a rare entity, especially for public school systems. LEA is welcomed in dozens of classrooms on a regular basis because field trips and hands-on experiences are in decline. We use the nation’s Next Generation Science Standards to design our curriculum. These materials are readily shared with other groups and schools throughout Maine. Our programs are free, allowing schools to use their limited funds for such necessities as program transportation. In a state as rich as Maine is in natural resources, it is ironic that so few schools have this opportunity.

The best outcome would be a breakthrough in our understanding of “tipping points” for lake water quality and thus the ability to predict and avert problems. While this may seem optimistic, we need to consider the impact of combining the knowledge base that currently exists but is not shared. As our advisory board has already demonstrated, sharing this knowledge and developing strategic research questions will lead to an escalation of understanding. This, in turn, will allow us to better focus the next generation of work to restructure lake testing protocols, upgrade standards and change behaviors.