For decades, Lakes Environmental Association (LEA) has watched over the water quality of lakes in the greater Bridgton area by making measurements and collecting water samples during late spring through early fall. Wintertime was mostly ignored due to challenging work conditions and the long-held perception that lakes are dormant during the cold, ice-covered period. More recently, the scientific community has challenged that perception through a growing number of studies that highlight the importance of evaluating winter-time lake conditions and linking those to overall lake health. Climate change plays a large role in the increased interest in winter lake conditions. Long-term records of lake freeze and break-up dates show that ice cover periods have decreased significantly for many places. Less time with ice cover has and will lead to a reduction or loss of cultural and recreational activities. The impact on water quality throughout the year from a reduction or loss of ice cover is not as well known. So to fill that void, researchers have increased efforts to study lakes during winter and improve basic understanding of winter conditions and how those might link to open water periods. LEA has joined in that effort to make wintertime field work a more regular part of lake monitoring. Our staff began detailed winter field work in 2018 with nine trips to a total of four of our service-area lakes. The total trip number doubled in the next year with six lakes visited. We made 13 trips with 7 different lakes in 2020, 29 trips with 11 different lakes in 2021, and 32 trips with 13 different lakes in 2022.

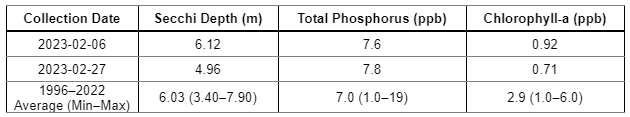

2023 was the third year we visited McWain Pond in winter. The water column was stable based on a gradual temperature increase with depth. By the second visit, overall temperature increased and constant temperature between 1.5 and 4 m indicated some mixing. Dissolved oxygen (DO) decreased with depth and slightly with time. Even though the bottom water remained oxygenated, DO was the lowest yet over the three years. Chlorophyll was generally low and declined with depth. Secchi depth was about average on the first visit and below the long-term average by a meter on the second. Phosphorus was a bit above average, and chlorophyll-a was below average and even lower than the long-term minimum.

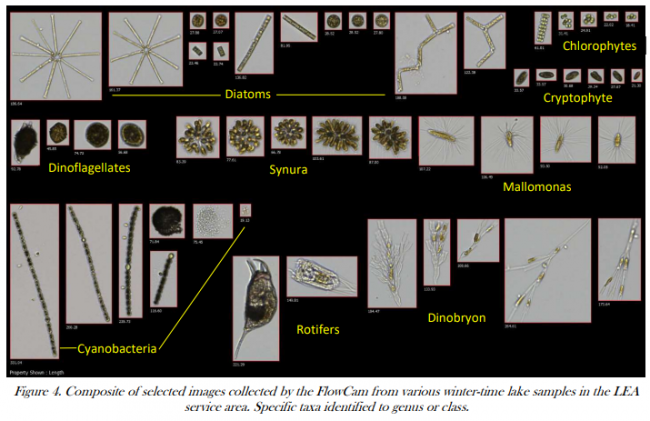

We used our FlowCam analyzer to characterize the taxa that make up the lake algae community in winter. Quantitative data is not presented here, since we have yet to finish fine tuning the classification process. We did capture images of several abundant and charismatic species or groups (Fig. 4), including diatoms, Mallomonas and Synura (Synurophyceae), Dinobryon (Chrysophyceae or “Golden Brown”), cyanobacteria, dinoflagellates, cryptophytes, and chorophytes (“Greens”). Several of these taxa are capable of deriving nutrition from organic matter and microbial prey in addition to photosynthesis, which makes sense in the light limited conditions of winter. The FlowCam also captured some images of rotifers, part of the non-photosynthetic grazing community (zooplankton).